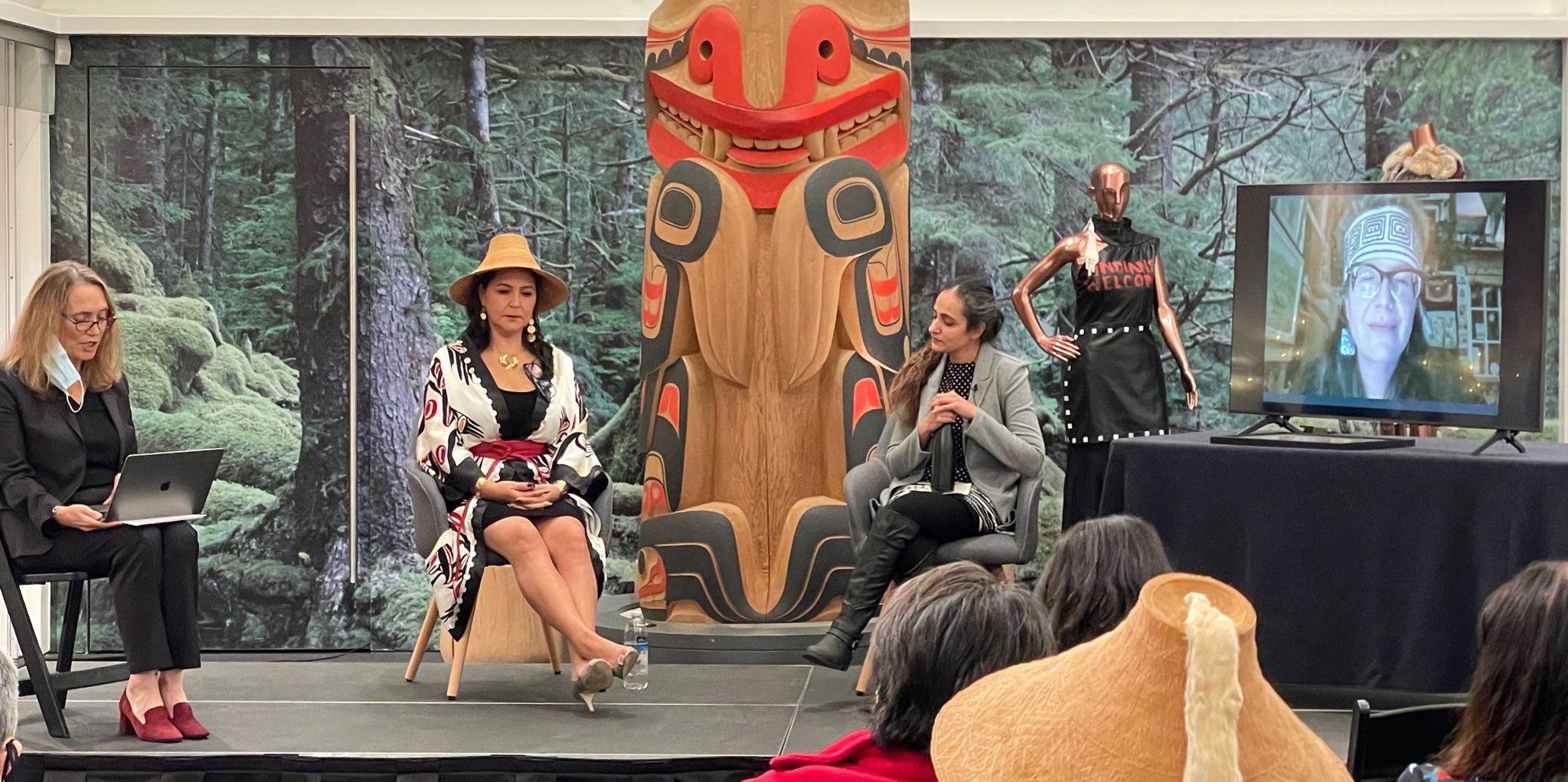

Sharanjit (Sharn) Kaur Sandhra being interviewed for the opening of the ‘We Are Hockey’ exhibit at the Sikh Heritage Museum in 2019. Image Courtesy of the South Asian Studies Institute.

Sharanjit (Sharn) Kaur Sandhra wears many hats. Not only is she an emerging scholar studying Asian diasporic and transnational affective voice at UBC History, she is also a sessional lecturer and staff member at the University of the Fraser Valley, a co-curator at the Sikh Heritage Museum in Abbotsford, and a mother to two young boys, aged 10 and 12.

As a Sikh woman pursuing a PhD in a discipline that hasn’t always been accepting or encouraging of scholarship from women, and especially women of colour, Sandhra has had to fight for every one of her accomplishments and triumphs.

The challenges she’s had to overcome have only strengthened her resolve to carve out a path for herself and those who will inevitably come after. “I love the imagination that History encourages, how the archives are places that are constantly challenged, and how I can teach, utilize, and display those histories to alter people’s perceptions of the past, and thereby change the pathways of the future.”

Unboxing Museums

Sandhra studies museums as spaces of belonging, and her interest in public history came from her curatorial work at the Sikh Heritage Museum within the Gur Sikh Temple, which is a National Historic Site of Canada. “My work in these spaces taught me the power of counter histories and the power of belonging through these spaces, which are otherwise ignored in colonial public history. The Gurdwara has become my living and breathing space of belonging. It was because of the work I did in the Sikh Heritage Museum that I was able to persist and continue my studies during some of my lowest moments in the program.”

For her PhD dissertation, Sandhra interviewed patrons at three museums, including the Gur Sikh Temple and Sikh Heritage Museum, the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, and the Burnaby Village Museum. Her goal is to understand how these museum spaces elicit narratives of belonging for racialized visitors. “I wanted to look at exactly the kinds of words, phrases, and repetition of words visitors use to describe their experience to forge a pathway for colonial museums so they can foster the same sense of belonging for racialized visitors. It’s time to decentre whiteness.”

Sandhra addressing attendees at the exhibit opening, ‘We Are Hockey’ at the Sikh Heritage Museum. Image courtesy of the South Asian Studies Institute

To Sandhra, the museum is a structure that is part of an ongoing legacy of colonialism and theft borne of the Enlightenment Era. “The museum was founded as a boxing in of stolen artefacts and of people’s histories,” she says, and too often, this is done through a white gaze despite community consultations. “When we look at the most powerful museums across the world, a majority of them are led by white folks at all levels, from the board of directors, to the curators, and to the marketers. These people are in positions of immense power, and they are crafting stories about communities they don’t belong to.”

On an experiential level, the lack of diversity in museum curation means there is often a disconnect in how racialized visitors relate to the exhibits on display. “My research revealed that when we write about ourselves, we aren’t drawn to trauma. White people may like to voyeurize us and our experiences, but we ourselves are drawn to different things,” says Sandhra, who emphasizes the importance of cultivating opportunities for racialized communities to tell their own stories in ways that are meaningful to them. “I found that the racialized visitors weren’t drawn to the stories of racism, trauma, or even the tired trope of resilience. They were drawn to stories about everyday life, like gardening, for example.”

Curating Spaces of Belonging in Classrooms

Sandhra’s approach in her classrooms is informed by her own lived experiences, including being an older student. “I was 30 years old when I started my PhD. The age difference, along with my Sikh identity and motherhood, was another divide I felt as a student, and I was made to believe somehow that even though I had more lived experience, it was lesser than.”

“I think part of the role of faculty is to understand the nuances of the diversities of students, and students with different age, gender, or racial identities,” says Sandhra, as she reflects on the importance of having guidance and support from her supervisor and committee members. “I belong very much in this department and in this moment, and I challenge what this department and discipline has always been used to.”

“Now, in my own classrooms, I strive to create the kind of environment where students can feel safe opening up to me,” says Sandhra.

“No longer can we just teach as though we are only here to teach our discipline, and not embed our students within the learning process through their lived experiences. A good instructor will see students for their whole identity and incorporate that into the classroom.”

The Path Forward

As a sessional lecturer who teaches many survey-based Canadian History courses, Sandhra recognizes the importance of highlighting texts and resources that engage meaningfully with the histories of resistance and power from racialized communities. “What we see in Heritage Minute videos, or widely used textbooks, is white-washed nostalgic versions of pioneer settler histories,” she says. “Yes, there are iconic resources that provide more detailed perspectives through a decolonized, and anti-racist lens, but they don’t always centre the everyday stories of racialized people. The teaching of these narratives and histories need to become part of the norm, as opposed to specialized tropes. Scholars of colour are better equipped to tell these stories in their entirety, not only through our research and lived experiences, but through the meaningful relationships we are forging with each other.”

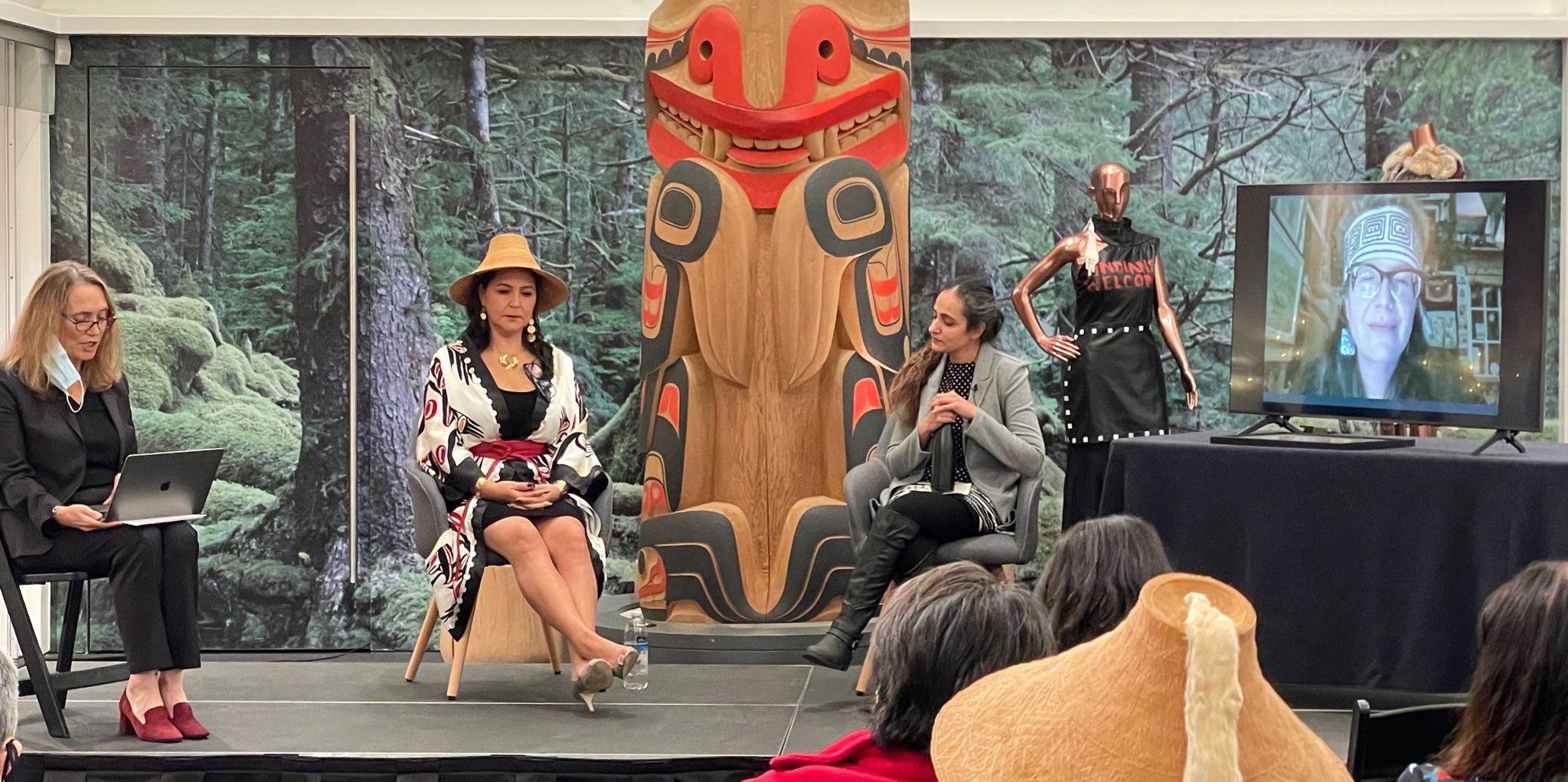

Sandhra in the panel discussion portion of the 2021 Sterling Prize Ceremony and Lecture with Sdahl K’awaas (Lucy Bell). From left: moderator Catherine Dauvergne, Lucy Bell, Sharn Sandhra, and Jisgang (Nika Collison) via Zoom. Image courtesy of the SFU Public Square.

When asked about her advice for others who want to carve out their own paths in public history, Sandhra says it’s important to strengthen connections and patterns of solidarities with those who share identities and experiences. “We live in a critical moment within museums and other spaces of public history. It’s a moment to be a part of the changes and challenges, rather than adhering to and reinforcing the same structures and methodologies that are themselves part of the problem. I’m excited to be part of that wave of creative energy and scholarship that continues to drive forth change, and I don’t plan on losing any energy.”