“I feel that it’s a moment when all of history is kind of rising up and being revealed before us, and we’re provoked to think about a million different questions.” – Robert Brain.

How has history been impacted by pandemics? How do we understand pandemics, and how do we study them? How do historians interact with the study of disease?

Four UBC history professors sat down (over Zoom) to examine historiography and epidemiology in light of COVID-19, all with different perspectives on the history of disease.

Dr. Heidi Tworek is a historian of media, international organizations, and health communications. Her recent publications include News from Germany: The Competition to Control World Communications, 1900-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019) and “Communicable Disease: Information, Health, and Globalization in the Interwar Period,” American Historical Review (2019)..

John Christopoulos studies society and culture in early modern Europe, as well as pre-modern medicine. He has published studies on health and the body in early modern Italy and his book, Abortion in Early Modern Italy, is forthcoming this year with Harvard University Press.

Robert Brain’s field is the history of science, technology, medicine, and European cultural history. His recent work includes The Pulse of Modernism: Physiological Aesthetics in Fin-de Siècle Europe (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015), an examination of the relations of the arts and the sciences in turn of the century Europe.

Tim Brook is a historian of ancient and modern China and international history. His recent work includes Great State: China and the World (London: Profile Books, 2019), an examination of China’s international relations since the 13th century.

In this virtual roundtable, they brought their respective historical perspectives to the current crisis to discuss what understanding the history of disease means during COVID-19.

How has the pandemic impacted or interacted with your field of study? Has it illuminated any aspects of your field or caused you to see it in a different light? Has anything you study gained new relevancy?What is the role of a historian in a pandemic? How have historians responded to COVID-19?

John Christopolous:

One thing that experiencing COVID-19 has made me appreciate is that the society and people that I study lived with the regular occurrence of epidemic disease in their lives, and by this I mean plague.

There was always plague somewhere in Europe from the 1340s until the 18th century, and even though everyone who works on medieval and early modern Europe and the Mediterranean knows this, we’re often guilty of not giving it the gravity that it deserves. Plague shaped probably every aspect of life. It was a fact of life and so were the crises and transformations that it brought; mass mortality, economic catastrophe, social and cultural breaks, etc. Plague and its consequences were expected and they were regular. While people certainly suffered from plague and its aftermaths, they also learned how to live with it. This shows the remarkable resilience of early modern societies.

Robert Brain:

What am I interested in with epidemics of the 19th century was the ways in which they provoked a whole new approach to medicine, which came to be called social medicine, which is largely the idea that the conditions of health and disease – social conditions, demographics, inequality, all these things produce the outcomes of disease in society.

But in the 19th century, people who did this were doing this with epidemics in mind as much as chronic conditions. Rudolf Virchow, one of the founders of this way of thinking, said ‘every society gets the epidemic it deserves’. So when looking at a society within any particular epidemic one has to ask the question, what is it about the shape of our society that allows a disease to express itself in this way, that allows this kind of disease to get through our defenses?

It strikes blind spots in a society. It hits its vulnerabilities and reveals things that are hidden or neglected and so on. That was the same kind of question that people were asking of AIDS, for example, in the 1980s.

One of the things that’s very interesting to me about the current crisis, is the kind of extreme condition of globalization that we live in – it’s a prime factor of this kind of disease. I’ve been thinking a lot about globalization and its relationship to different categories of disease, particularly chronic disease, non-infectious diseases like diabetes

“Understanding AIDS”, booklet printed by the US government, 1988. Photo: U.S. Surgeon General and the Centers for Disease Control, U.S. Public Health Services / Public domain

and metabolic syndromes. In the government of mass disease, people often make a distinction between a sentinel system, a warning system anticipating infectious disease; and an…actuarial (system), which is based on the idea that we’re looking at vital statistics and numbers and quantifying the different kinds of conditions of society. In certain instances like global AIDS or AIDS in Africa, these two models actually blur together and run together, and there are ways in which the current epidemic also does too.

It’s hardly surprising that the world’s most important chronic disease is also the most important risk factor for this present epidemic–diabetes and hypertension–and all the core comorbidities that surround metabolic syndrome. So the map of morbidity and mortality of these diseases reflects, to a large degree, the similar kinds of mapping that we have of diabetes and other chronic diseases. This is one of the ways that I’ve been thinking about the way that institutions have managed the two different epidemics. Because, to a large extent, infectious disease is often walled off epidemiologically from these other kinds of problems, but in fact this disease is reminding us that these walls are problematic.

I feel that it’s a moment when all of history is kind of rising up and being revealed before us, and we’re provoked to think about a million different questions.

Timothy Brook:

The question of the role of the historian and pandemic has gotten me thinking about my own role as a historian of the contemporary world in which I live, and I’ve been thinking about this as a China historian. Let me go back to the 14th century. We have extraordinarily detailed accounts, written by chroniclers at the time, of what the experience of the Black Death was like in the Middle East, in Egypt and in Europe. These are the sources that we as historians go back to in order to try and understand the spread of the plague. In the 14th century China experienced roughly 12 years of terrible epidemics, shortly after the Black Death broke in Europe. And yet the Chinese record contains no descriptive accounts of what that experience was like.

So as a historian of China who is interested in global history, I find myself puzzled by the fact that the Chinese record is virtually empty and the European record is so full. We end up writing history on the basis of the sources available to us. We have a very rich historiography for the Black Death. It’s a common fact everybody learns about it in school. And yet, there’s nothing from the Chinese case, except the odd little bit of information here and there that I’ve been able to pull together. There is no contemporary literature on what it was like to experience that pandemic.

So I find myself in 2020 thinking, ‘what is my role in this story, and this time around?’ And one of the things I started doing early on was to try and keep a record of what was happening in China as events started to unfold there, because as we move forward in time, it is harder to go back and reconstruct the events of January and February, given the interest of the Chinese government in crafting a story that is positive for its image.

As historians, and as direct observers, we are all experiencing this event both as a medical crisis, but also as a case of storytelling, in which the powerful actors in the story are regularly rewriting the story as quickly as they possibly can. The US Republican Party and the Chinese Communist Party are surprisingly similar in the way in which they want to grab hold of the event, and make it a story that has the creation of what will prove to be an incomplete historical account that we’re going to have of this pandemic, which is why I’ve tried to do what I can to keep track of events as they’re unfolding.

Heidi Tworek:

That actually ties in quite well to what I was going to say. I don’t think anybody could have predicted the outbreak that we have ended up with. But when we as historians try to understand structural conditions, we can foresee certain things that might unfold if a pandemic breaks out.

I’ve been working for some years on the history of health communications during epidemics, and the inability to communicate in certain ways. The difficulties the WHO has experienced, were in many ways, unfortunately, predictable, if one had looked back at history. I say this not as the historian who can tell you what the future will bring, but I can at least give a sense of why it is that certain difficulties are unfolding in the ways that they do. That the WHO would be politicized, for example, is something that we could understand if we looked at the history of international health organizations.

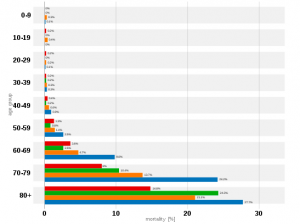

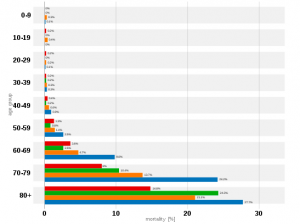

The other type of rewriting and confusion that is happening is around the question of data and information. How do we create comparable statistics? Statistics are leading countries to make decisions on the types of lockdowns they have and whether they will release them. Within those statistics, many of the exact same problems existed when international epidemiological systems were created in the interwar period. Namely, the difficulty of who is collecting statistics, how do you standardize them, how do you ensure that they’re correct.

For me, most importantly, there is the fact that we fall into a trap of looking only at statistics, and not at human stories. It’s incredibly striking how few stories we have of people who have succumbed to this disease. We are all in a very bizarre way, obsessed with what seems like almost leader tables of which country has more or less deaths- that dehumanizes in a truly horrifying fashion. And this, to me, goes back to the century-long history of the attempt to try and conquer disease internationally through statistics, and not stories.

Table showing COVID-19 infections by age group and country, as of 28th April 2020. China: red, South Korea: green, Italy: orange, Spain: blue. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Attomir / CC0

Timothy Brook:

Yes, those tables remind me of the Olympics. In the same way in which we organize international sports along national lines, we’ve turned this event into a national competition.

Heidi Tworek:

There’s actually a very interesting history of rankings and what rankings do and how rankings function. In the 18th century, for example, Germans would rank literary figures. Tables can affect human behaviour. This has real consequences for how we understand this pandemic and how we actually act at this moment.

One word I’ve seen cropping up a lot in regards to COVID-19 is ‘unprecedented’. Do you agree the pandemic is unprecedented/the first of its kind?

John Christopoulos:

An almost instinctive response that I have, and many people have, is to liken every epidemic disease to “The Plague.” It’s the standard against which we automatically measure an epidemic disease. Of course there are similarities between COVID-19 and plague, but there are obviously very important differences, and it’s important to disentangle them.

COVID-19 is unprecedented in the speed that it traveled. Plague, or to be precise, the second plague pandemic, emerged somewhere in Central Asia in the 1330s. The earliest record we have of it in Western Europe is Messina in Sicily in 1347. From there it spread throughout the Italian peninsula, throughout the Mediterranean and Europe. I believe the first mention of plague in England is from 1348 or 1349, about a year or so after it arrived in Messina. That is very quick in the medieval and early modern world. The movement of plague shows us how well connected medieval Eurasia was, which is something that we often underestimate. But when we try to put this spread into the context of the spread of COVID-19, it’s not really comparable. Weeks for COVID-19 to spread throughout the whole world.

Another thing that strikes me as unprecedented is the nature of communication around COVID-19. Early modern Europe had a robust network of communications. Merchants sent letters from wherever they were back home, diplomats conveyed information. Plague was often a topic of conversation. People wanted and needed to know where plague was in order to prevent it from entering their home.

But as robust as these networks were, they are nowhere near as impressive as what we’re seeing with COVID-19. It’s unprecedented in terms of communication, but also our level of knowledge about it. Everyday we are exposed to new information about the virus, its spread, the effects it’s having on our healthcare systems, economy, and politics.

There are of course important similarities. In the 1340s Europeans were hit with something new, something unexpected, confusing and devastating. With COVID-19, we have also been hit with something new, unexpected, confusing and devastating. Medieval and early modern people did not know what plague was but they tried to discover its causes and fight against it – there were many competing and overlapping ideas. We are doing the same; we are also debating the causes of the virus and arguing over how best to fit against it. Pre-modern Europeans thought plague was transmitted in the air and thought that sanitation, good hygiene, and quarantine were the best means to contain it; we are trying to contain COVID-19 by washing our hands, wearing masks, disinfecting everything and by socially isolating.

They didn’t know how long plague would last, how it would end, what its short and long-term effects would be; we are facing all these uncertainties with COVID-19. But one major, major difference that does need to be stated is that COVID-19 is not nearly as fatal as the plague was. So making those comparisons, while they might come instinctively, must be scrutinized. Plague killed 50% and often much more of people that were affected. We are lucky that COVID-19 is nowhere near as fatal.

Timothy Brook:

I agree and simultaneously disagree. As a 21st century person, going back and watching how fast the Black Death actually moved in the 14th century, I find it stunningly quick. That we find its progress slow reflects our natural assumption that we in the present inhabit a busy active world, and that back in the 14th century you couldn’t get anywhere without taking a week to do it. What impresses me about the Black Death and the 14th century is the speed with which it moved, relative to the practices of the time. Our long-distance travel is no longer constrained by the impediments entailed by crossing land and crossing water. We now travel by air, which means that moving a pandemic can be done in an eight hour flight, instead of an eight month voyage, which changes everything. It’s curious though, how Italy comes up as the European nexus point in both the Black Death and COVID-19.

Our knowledge, also, changes the way in which people talk about this pandemic. The big difference is that we now can speak in terms of the genomic sequencing of viruses rather than random outbreaks or the Wrath of God. The scientific basis for understanding how a disease mutates, how the body responds to it, how the body can create immunities to it, has changed. Accordingly, we’re experiencing COVID-19 differently than say, the world experienced the Spanish flu. I think it’s fair to say that if we didn’t have antibiotics, and we didn’t have ICU protocols that we have today, COVID-19 would be killing us at the same rate that the Spanish flu did so.

Our experience of COVID-19 is different because we can be intubated, for example, enabling us to weather respiratory failure in a way which was impossible during the Spanish flu. If the plague erupted pandemically again, heavy enough doses of antibiotics and intensive care responses would probably keep most of us alive now. That to me as a historian is the fascinating thing: how we’ve kind of reset so much of the basic understanding of the science of disease and on that basis developed such different therapies. Medical responses to disease make it almost impossible to make the comparison with what happened in the past.

Robert Brain:

I kind of disagree. On the one hand, you can’t help but be impressed by how, in mid January, the genome for the virus had been identified and sequenced. On the other hand, while we know an enormous amount about the disease, I’m struck by our utter helplessness in the face of it.

The intubation doesn’t work very well. It’s a bit like a lot of medieval plague cures- the intubation is sometimes worse than the disease itself. As so often happens with disease, with new pathogens, we don’t know it well enough, and we don’t understand it. We know a lot about it, but by the time that we know enough to do something medically against it, like have a vaccine or have effective viral treatments and so on, we will probably have it under control, socially, to a large degree. And that’s been the pattern with diseases in the past. That was true of AIDS, for the most part.

I would say about the “unprecedented” question, it often happens that there’s incredible amnesia about epidemics that sets in. People often say epidemics come in with a bang and they end with a whimper. At the moment when people are tallying up the lessons from epidemics, nobody’s paying attention. Maybe a few experts. Because everybody’s fed up and sick of it, and wants to move on and forget about it. And so, for example, people don’t remember the Asian flu epidemic of 1958 that killed over a million people worldwide, 100,000 in the United States. The unprecedented quality is largely [due to] both this blind spot and this relative amnesia that sets in.

But at the same time, over the course of an epidemic, people begin to remember. Epidemics dredge up an enormous amount of memory of past epidemics. People suddenly read up; they remember; before they, in turn, forget. Again, it seems to be the pattern. People begin to try to manage and cognitively frame the seemingly random events that are happening around them over the course of an epidemic.

The speed of communications–someone came up with the term “pandemicity,” which describes this sense of connectedness–that the whole world feels in experiencing this at the same time, and having this common experience, looking at the same kinds of news feeds. I think that that may play out quite differently in the longer-term memory, because it will shape our collective sense of dealing with future problems like say, climate change, as well as a range of other structural problems in the world.

Heidi Tworek:

I’m struck by how some things I honestly did not expect to be important in a pandemic of the 21st century actually became so. The debate about masks also occurred during the Spanish flu, for example. The fact that ships, actually, in this case cruise ships, but in the past trade ships, were actually an incredibly important vector of this disease. I’m not sure the planes in some cases were as important as ships. If we now look at what’s happening in Taiwan, they had this epidemic under control; in mid-April it flared up again because of some sailors who disembarked.

U.S. naval hospital prepares to receive Spanish flu patients. Photo: Navy Medicine from Washington, DC, USA

Regarding the question of whether a pandemic is or isn’t recorded- one of the extraordinary things when you look at the League of Nations Health Organization is that they never mentioned the flu pandemic. It doesn’t exist as a written justification; and yet it’s there in everything that they do. This to me is another interesting part of what we see happen with many epidemics- that what people do afterwards is so informed by it, but they might not be writing about it all the time.

If we think about our current world, in the first emails we wrote, we probably used a coronavirus word, or COVID-19.Now everybody knows it’s happening, so we don’t write about it. This can illuminate how we try to understand the sources of the past- the way in which we all know about COVID-19, it is around us, and yet we aren’t constantly referencing it in quite the same ways.

One of the myths that I would like to bust is, with respect to my dear colleagues, the idea that somehow this is an unprecedented communications situation. The interwar period had wireless communication that moved around the world incredibly swiftly, and the experience of the flu did happen simultaneously for many people. With this pandemic, as with many others, we have a group of people who can experience it simultaneously in some fashion, and some people who are not within those networks- over a billion people who simply don’t have access to the Internet.

The perhaps more unprecedented aspect is the ability to have many communication platforms. But even platforms like YouTube or Facebook have cracked down on many of the conspiracy theories flying around. The idea that we have completely unfettered ability to express ourselves- it’s not true.

An example of conspiracy theories spread online that link 5G masts and COVID-19. Photo: Neil Hall/EPA

As well, I think there are different types of knowledge. This pandemic has highlighted that there is scientific knowledge, but then there’s also how it is implemented. The historians have a lot to say about why there are certain types of responses to pandemics in different places, and to remind everybody that the key conditions to the response here are often not the scientific, but the social, the economic, the political, and the interaction of these different factors. Even if the way in which this pandemic specifically unfolds is unique, the interplay of those factors, it seems, is something that we as historians can recognize.

How are past pandemics/epidemics remembered? Has the way past pandemics are perceived impacted current discourse around or responses to COVID-19?

Timothy Brook:

In China, there is no popular memory of pandemics in Chinese history. It’s just not something that is there. It’s been excluded from the educational curriculum, perhaps because the rest of the world has so much wanted to vilify China as the place from which epidemics arise and spread. The third plague pandemic, for example, sailed out of Hong Kong in 1894 to infect the world, and that gave China a very poor public reputation that wasn’t precisely China’s fault. In fact, genomic analysis now shows us that that form of the epidemic had to have originated from Europe. But China was vilified in the 1890s, as the place where disease just leaks out into the rest of the world.

Chinese village emptied by plague. Photo: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

China accordingly doesn’t want to have a memory of Chinese pandemics. In countervalence, we in the West want to look to foreign places as the locations in which disease arises – whether it’s through poor social practices or poor hygiene practices or a failure to understand basic medical hygiene. We want to offload our responsibility for pandemics and send it somewhere else in the world, and China is the place to do that.

This has been further complicated by the politics since late January about who should be made to take responsibility for what. To speak from a global biogenetic standpoint, China is not responsible for COVID-19. It just happens to be the place where it broke out. To even speak about there being a national responsibility for an epidemic is problematic. If a nation has responsibility, it is for its response to an outbreak. So our memory is our way in which we either create space, or don’t, for thinking creatively about the global situation we suddenly find ourselves in.

Robert Brain:

I’d like to revisit the point that the Black Death plague serves as a template for the way that we think about epidemics in general. I also think that it’s odd, because there have been so many other epidemics–yellow fever and cholera and typhus and smallpox–and yet the (Black Death) template keeps coming back. I think part of it has to do with the way in which the most devastating epidemics of the 19th century, the cholera epidemics, were seen through the lens of the Black Death.

When cholera came through Europe in 1832, Justus Hecker, a German medical historian and physician, wrote a book on the Black Death in the 14th century, that set the terms for understanding cholera. He said, in this book, the secret to understanding the cholera that afflicts us is the Black Death. He emphasized the disease’s Asiatic, ‘Oriental’ origins, and the path of the disease. The degraded environment in society that it hit was used as a kind of social critique.

So there’s a tradition of interpretation- the imagery of cholera in the 19th century is Gothic. And our imagery surrounding pestilence in general is Gothic.

John Christopoulos:

I think the image that most people have of plague in pre-modern Europe is one of mass death and catastrophe, superstition, ineffective medicine and scapegoating. Early modern Europeans believed that plague was a putrefaction of the air, water and soil, that it was caused by an astrological configuration, that God sent it in order to punish human beings for our sins.

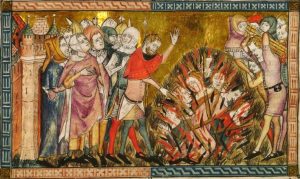

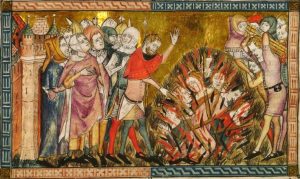

But they also thought that plague often came to Europe from the east, from in hotter and insalubrious climates, from the places where the infidels and heathens live. They believed that these people, usually Jews, Muslims, and also merchants and soldiers who interacted with them, brought the plague from these places into European Christian spaces. They also believed in conspiracy theories. People believed that Jews poisoned wells and that witches unleashed plague through their pacts with the devil.

Conspiracy theories and scapegoating people and societies for the onset and spread of plague is nothing new. Seeing how and why this was done, and confronting the brutal ways people suffered because of these beliefs in the past should teach us how wrong it is to scapegoat people and societies for COVID-19 in our present. As Tim said, China and the Chinese are not responsible for COVID-19 any more than Jewish people, Muslims, witches, ‘sinners,’ etc were responsible for the plague in medieval and early modern Europe.

Jews being burned at the stake in 1349. Image: Unknown author/Public domain

Heidi Tworek:

There are also ways in which remembering can be good, and there are ways in which the disease you pick as your comparator very much affects how you respond. One of the reasons why places like South Korea or Taiwan have had comparatively better responses is the memory of the recent SARS epidemic in 2003. Just as in the 19th century, the comparison between cholera and the Black Death affected not just aesthetics, but also where you thought the disease actually came from.

The comparison with something like Spanish flu can be very misleading because, in fact, it mainly attacked people between the ages of 20 and 40. This is hugely speculative, but that comparison may have turned us away from thinking about, for example, the problem of care homes, which turn out to be one of the major places where people are being infected with COVID-19. Remembering can be helpful if you’re comparing it with the right thing.

I see the basic skills of the historian coming back to play in this urgent moment- we always caution our students to think about why you’re comparing X with Y, and to consider both what we need to remember and whom we are leaving out of this story.

Robert Brain:

Adding to Singapore and Hong Kong and Taiwan, also, Canada had experience with SARS. I think one of the reasons for the excellent British Columbia response has been the memory of SARS. But it’s also worth noting as well that the Ontario response has not been as effective, in part because the lessons drawn from SARS were different from what was drawn here. Because quarantine was extremely controversial, there was some rioting. People drew different conclusions from the SARS epidemic in some key respects in Ontario and British Columbia.

Timothy Brook:

The memory of SARS also shaped how the Chinese government acted. Through the first half of January it explicitly ordered that medical personnel in Wuhan not use the word SARS. That triggerword should not appear anywhere, even in internal, private communication. You just could not use the word because it evoked the memory of how ineptly China handled SARS when it broke out in 2002, which was when the WHO came in and sorted them out. That was one of the WHO’s greatest moments in the last 50 years, bringing SARS under control.

Statue in Shenzhen Central Park, China, erected in memory of medical staff during the SARS outbreak. Photo: Sparktour / CC BY-SA

Robert Brain:

But at the same time, the Chinese public health infrastructure is light years away from what it was in the first SARS epidemic. And that is so they may not have wanted to use the term, but the effects of SARS are now being shown in the strength of the Chinese response, once they got going.

Timothy Brook:

True, but first, there were political hurdles to clear that should not have been there to impede the response. The doctors in Wuhan Central Hospital knew that they were looking at a SARS-like virus. By December 30, it was clear to them what they were up against, but political interference prevented their knowledge from being allowed out into the public realm. That gave China two weeks to fumble around and figure out what its political response was, which was just enough time for it then to become a global pandemic.

What aspect of the history of pandemics do you think is currently most misunderstood / needs to be better understood?

Heidi Tworek:

I think one of the things that’s been most misunderstood is the role of the World Health Organization (WHO). The misunderstanding that this is an organization that isn’t ultimately dependent upon nation-state members. Like any international organization, it is dependent upon states for its funding and its ability to investigate or coordinate information. I think that’s been forgotten.

Finally, to end on a positive note, I always do a lecture in my history of international relations on how the WHO helped to end smallpox in the 1970s. That is a story of how, in the height of many aspects of the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union cooperated through the WHO to create a mass vaccination program that ultimately ended smallpox, nearly two centuries after people like Thomas Jefferson hoped it would be eliminated by vaccinations.

The role of the WHO is complex. It is politicized in different ways, but sometimes it can be a space where deep antagonists can work together to solve problems.

Timothy Brook:

One of the things that has struck me this time around is that the focus of public discussion is very much on the economic costs. This may be because fewer people now have the economic security of salaries and benefits compared to 20 or 30 years ago. That we live in an economically more precarious international situation today shapes the story that’s running on the news every night, and this a time when states and private corporations have the resources to enable us to go through a year of pandemic without anybody suffering.

But there seems to be no way that has emerged to talk sensibly about the problem of the economy under the conditions that we’re in at the moment. This is one of many topics that the public media do not know how to talk about and that prevent the rest of us from having an intelligent discussion.

Robert Brain:

It’s worth pointing out that only one disease has been eradicated in the history of human beings through our conscious efforts: smallpox. Many of these diseases, we learned to live with them. AIDS certainly has more sufferers than ever before in certain parts of the world, and so on. The end to it won’t be a sharp end, it will be learning to live with it. It’ll become part of our lives. Part of our reality in some form or another. So it’s impossible to predict. In some way or another, we will learn to live with this.

John Christopoulos:

Anthony Van Dyck- Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-Stricken City of Palermo, 1624. Photo: Public domain

To go back to the beginning of our conversation, I’m most struck with how early modern Europeans appear to have lived with the regular occurrence of plague. I don’t mean to minimize the mortality rates and the devastation plague caused, especially during its onset in the mid 14th century and during the terrible outbreaks of the 17th century. But life did go on. Societies and cultures were not crushed. In fact, many thrived despite devastating plagues. The early modern centuries are marked by incredible intellectual, scientific and artistic achievements.

I think we have something to learn from that resilience. What worked for them? What social configurations or measures made outbreaks better or worse to manage? Let’s hope that COVID-19 is eradicated soon. But if not, if it stays with us, we have to learn to live with it. How do we deal with that insecurity?