Compilation of images History faculty chose to represent their 2023/2024 courses.

A History classroom is where students can visit the past to gain an understanding of the present. UBC History courses have no prerequisites, which means students are free to roam across time and space to follow their unique interests, regardless of prior knowledge about a subject.

Whether you are fascinated by the history of medieval Europe or photographic archives, feel more at home learning about the Middle East or about British Columbia, UBC History has a course just for you. Read on for a taste of UBC History courses offered during the 2023/2024 academic year, and check out our full catalogue of courses designed to enrich your university experience. Happy course registration!

HIST 100: What is History?

One of the earliest surviving fragments of the Gospel of Matthew, Papyrus 24, preserved at Sackler Library, Oxford University. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Instructor: Dr. Josh Timmermann (he/him/his)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

This ancient papyrus scrap of the Gospel of Matthew is one of the canonical gospels, telling one version of the story of Jesus of Nazareth. It represents, in a rather striking way, how fragmentary and partial the sources for “History” often are. It also represents the complex work that historians have to do to analyze, interpret, and somehow flesh out a fuller sense of the past based on faintly remembered stories.

What can students expect from HIST 100: What is History?

In this introductory course, students can expect a wide variety of readings concerning the history of history-writing from antiquity to modern times and the methodology and theory of history. We will look at a wide range of case studies, including the “Historical Jesus,” the “Fall” of the Roman Empire, the mythologized encounter of Pocahontas and Smith, and the Holocaust as a representable (or perhaps uniquely unrepresentable) event.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I am most looking forward to introducing students to forms of, and approaches to, History that they are unlikely to have encountered before university. I also want to show them, through famous case studies, the kinds of problems, challenges, and debates with which historians must contend.

HIST 101: World History to Oceanic Contact (Global History before 1500 CE)

Poster featuring objects that will be examined during the course. Image via Sara Ann Knutson.

Instructor: Dr. Sara Ann Knutson (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

The course poster features some objects that we will examine in the course. We will study materials as well as primary source texts and oral traditions. I selected these images to showcase how multidisciplinary the course is, and to give a glimpse of the wide-ranging societies around the world that we will learn from.

What can students expect from HIST 101: World History to Oceanic Contact (Global History before 1500 CE)?

One of the goals of this course is to help students recognize that the premodern global past was not a Eurocentric phenomenon. We will pursue a greater variety of perspectives than what European historians have traditionally examined. There will be no memorization of random historical facts. Instead, students will learn how to think “historically” and how to critically analyze primary source readings. Most tutorial readings will be short primary sources to keep the reading load manageable from week to week. The main basis for assessment in this course is a capstone timeline project, which students develop through smaller assignments along the way with feedback from the teaching team!

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I love teaching this course because it offers something to anyone interested in the past, whether History is your intended major or if you have never taken a History course before. My multidisciplinary training in History, Archaeology, and Anthropology informs my teaching and students will see aspects from each of those disciplines in the course. I am most looking forward to the storytelling aspects of this course and seeing how students choose to creatively develop their final projects.

HIST 102: World History from 1500 to the Twentieth Century

Matteo Ricci and Paolo Xu Guangqi depicted together in a 1688 Dutch translation of China Illustrata (1667) by the Jesuit writer Athanasius Kircher. Image via Wikipedia.

Instructor: Dr. Josh Timmermann (he/him/his)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

This is an image of the Italian missionary and scholar Matteo Ricci and his most famous convert and collaborator, “Paolo” Xu Guangqi. It encapsulates well the complicated, contingent, often surprising interaction of disparate cultures across the early modern world. There’s a lot going on in this image, and it demands to be carefully “unpacked,” which is exactly what we will do in this course.

What can students expect from this course on world history?

Students will read a variety of historical primary sources, ranging from poetry and philosophy to political treatises and biographical writings. These texts will be complemented by pertinent recent studies by historians. We’ll also be watching some movies and considering the potential of film to represent and immerse us in the lived worlds of the past.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I am most looking forward to showing students the deeply and sometimes wonderfully strange (from our vantage point) the world(s) of the not-so-distant past, in particular, the “thought worlds” inhabited by people like Ricci and Xu. I’m excited to introduce students to the range of methods by which historians can, to some extent, come to better understand those seemingly strange, highly opaque worlds.

HIST 201: History through Photographs

''A woman in kago and two kago carriers'' by Kusakabe Kimbei (1890s).

Instructor: Dr. Kelly McCormick (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

This photograph represents the challenges that photographers like Kusakabe Kimbei faced in the late 19th century in representing communities in ways that would appeal to both local and international audiences In this course, we will examine photographs – from glass plate photographs made in the 1870s in Japan to snapshots from family albums made by immigrant families in Vancouver to protest photographs made in the 1960s and 2020 – and as sources of important histories of colonialism, immigration, gender identity, consumer culture, and community formation.

What can students expect from this course at the intersection of history and photography?

Our focus is on examining photographs in archives and having exploratory discussions about these fascinating images with each other. To help enrich these conversations, each week students will read one article or book chapter related to the photographs. Assignments will include writing a biography of an individual photograph selected from one of our archives and a final essay with options to write about your own family histories through photographs.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

In this class each week we examine a new archive of photographs to understand what histories they hold, or in some cases, to uncover what histories they seek to hide. We pair our examination of the past with contemporary artists’ reactions to historical photographs for examples of ways that we might critically repair and re-read photographs that were made by colonial officials, and photographs that perpetuate stereotypes and forms of violence. You will finish this class with the power of critical visual literacy and a new understanding of the power of photography!

HIST 270A: China in World History

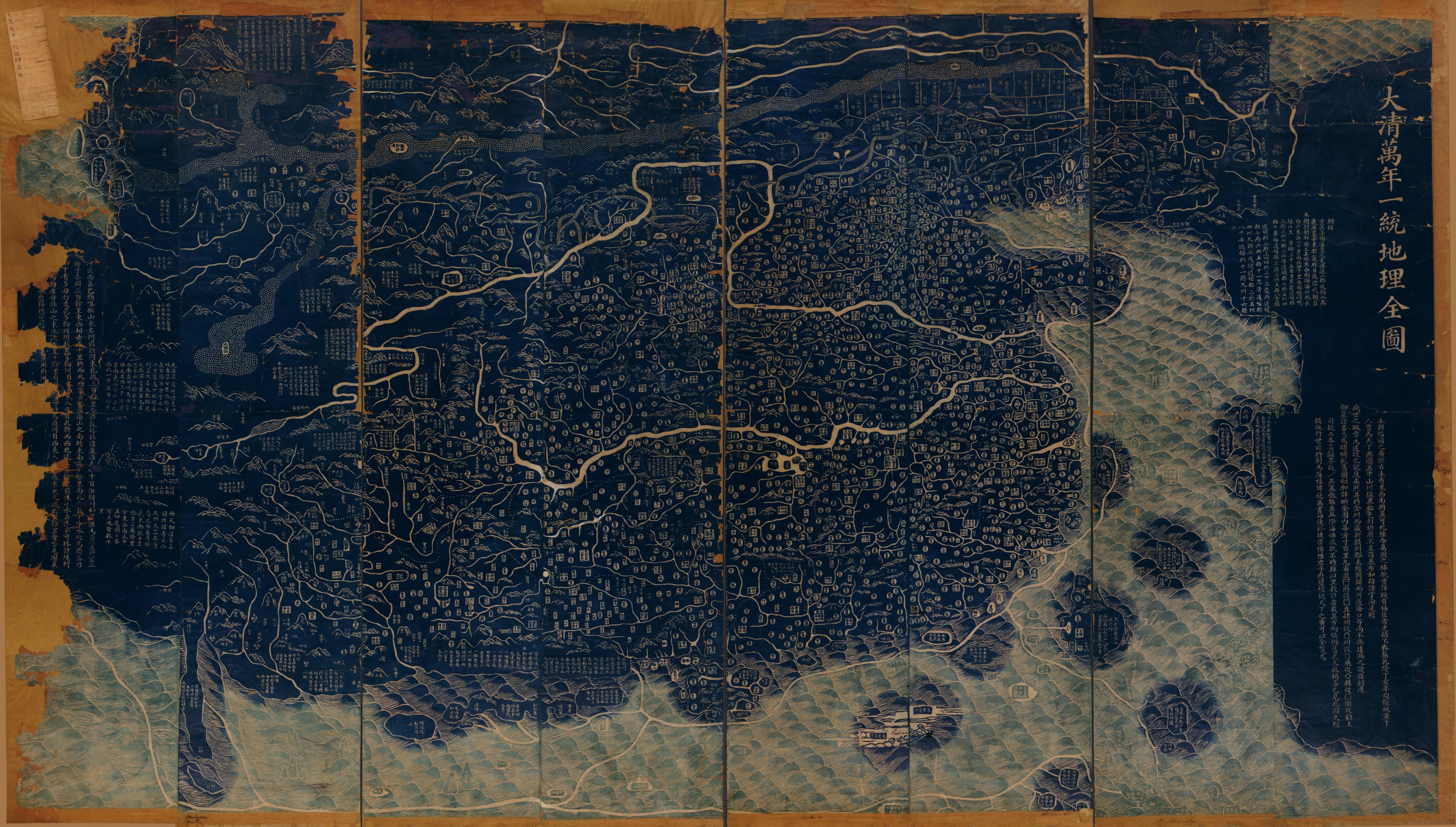

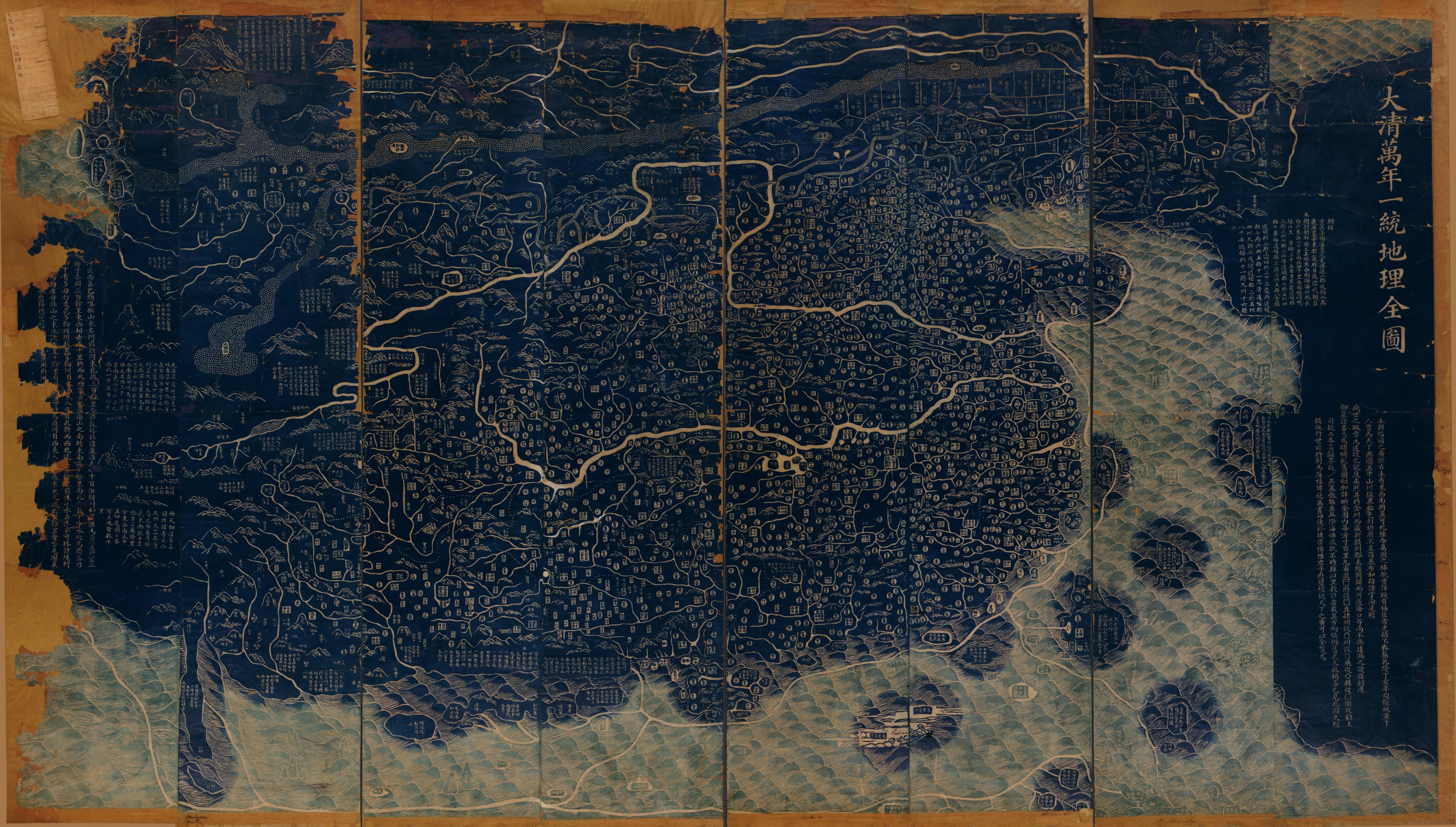

Huang Qianren, Active 18th Century. Complete and general map of the everlasting Great Qing. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Instructor: Dr. Sarah Basham (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

This map (c. 1814/1816) captures a Qing-dynasty cartographer’s perception of the Chinese empire and its surroundings. In this snapshot, we see foreshadowing of the People’s Republic of China and its neighbours. We’re going to explore how this vast, fluid space became China, and how its people interacted with others from prehistory to the present.

What can students expect from this course about China in world history?

We’ll use China in world history as our vehicle to gain research skills. Zero background in Chinese history is required to take this course. Weekly assignments build to an end-of-term bibliography assignment. Students learn to confidently find, cite, summarize, and interpret sources, and ask historical questions like, “how did China define itself (and others) across time?”

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I’m excited to think collectively with students about how humans define themselves and others, and the mechanisms through which societies, individuals, and groups change and influence each other.

HIST 336: Imperial and Colonial Archaeology and Museums

A shield made of hide, with a pendant made of lion's mane from Maqdala, Ethiopia. The Trustees of the British Museum. Used under a Creative Commons License.

Instructor: Dr. Bonnie Effros (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

The British Museum’s collection includes around 80 manuscripts, regalia, sacred vessels, and liturgical equipment from Maqdala, now known as Amba Mariam, in northern Ethiopia. Other pieces from the same collection are in the Victoria and Albert Museum. They arrived in London after a British expeditionary force pillaged the materials from the imperial treasury, library and church at Maqdala in 1868 and then auctioned off the precious artifacts. This course asks: what are some of the implications of plundered goods being exhibited in London as “art” in some of the most prestigious and well respected art museums? Students will discuss the impact of imperial plunder (whether through archaeology or war) on national collections in Europe, North America, and Asia, and why these sites are so contested.

What can students expect from this course at the intersection of archaeology, history, and museums?

We will have weekly readings that give some background in antiquities law and the development of archaeology and museum culture in the context of nineteenth-century imperialism and colonialism. From there, we will move on to discuss specific cases such as classical archaeology, Egyptology, the collection of Indigenous artefacts in North America, “human zoos” that were a part of colonial culture intended to show the superiority of certain races, and many other practices that played a profound role in creating museum collections.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

So much of what we take for granted in museums’ cultural role reflects the imperial and colonial power that underlies the building of these collections. Teaching this course is a profound experience. I’m excited to work with students to think about how objects convey identity as well as help define what we think about as “civilization”. Over the course of the semester, each student will learn to write object labels, critique an existing exhibition, and learn how to create their own digital museum exhibition.

HIST353B: The Abbasids: History, Heritage, and Memory

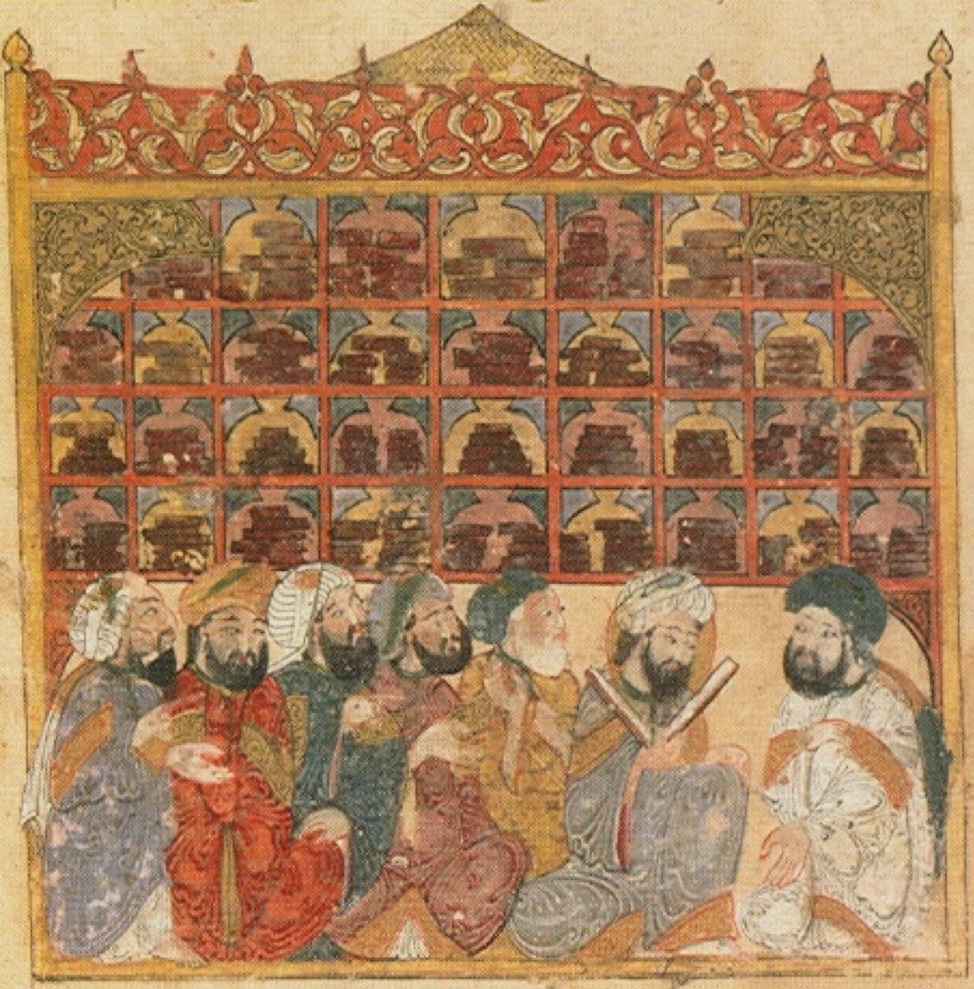

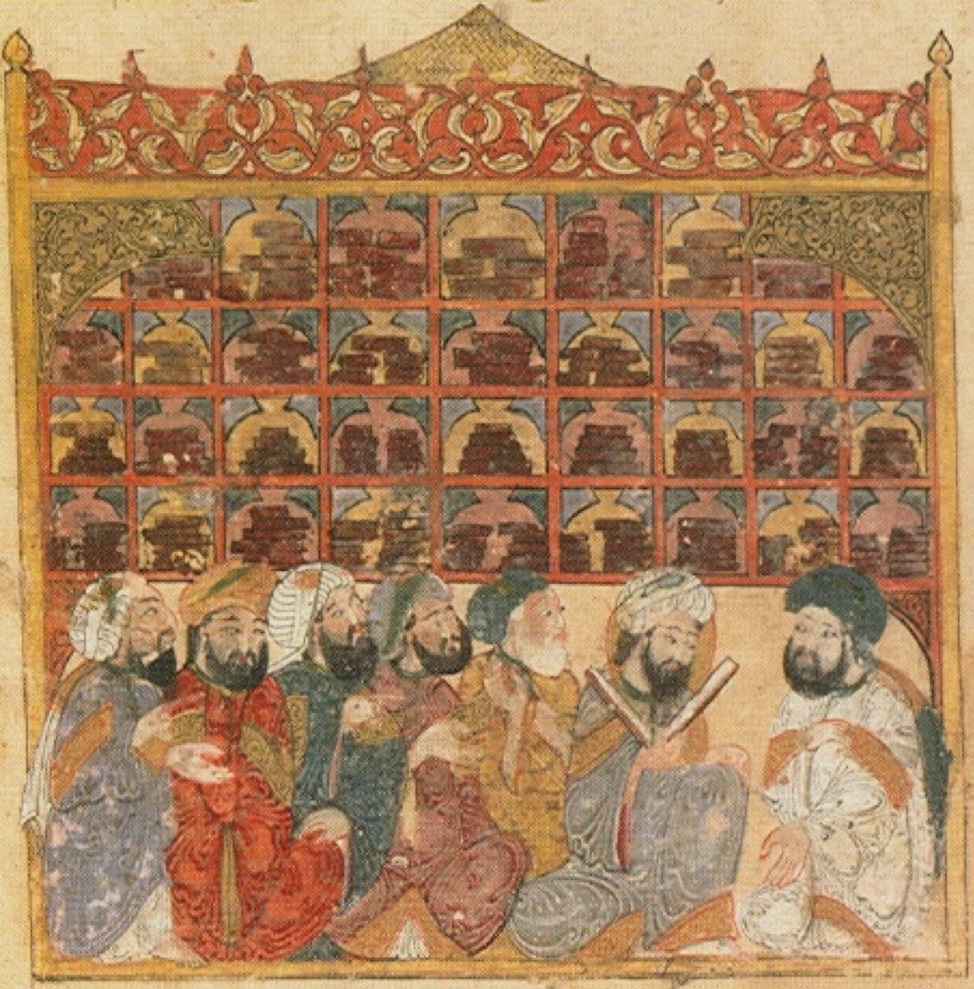

Abbasid-era scholars in the 'House of Wisdom', a centre of learning, in Baghdad. Image from book 'Maqamat al-Hariri'; Image artist: Yahya al-Wasiti, 1237 CE.

Instructor: Dr. Sara Ann Knutson (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

The Abbasid Caliphate is considered the Golden Age of the Islamic World for its intellectual and artistic achievements. This image speaks to the emergence of Baghdad as an intellectual centre. In our own centre of learning, we will examine the Abbasid past and how its legacy resonates still today.

What can students expect from studying the Abbasids?

This course is about the political, economic, social, and cultural history of the Abbasids and their contributions to the Islamic World and beyond. We will investigate how history of the Abbasids lives on in our present day in textual and material archives and in intangible heritage practices. As historians, we will engage scholarly debates, digital methods, public-facing history, and current discussions on heritage and memory to help us analyze the Islamic past and its ongoing relevance to our world today. No prior knowledge of the Islamic World or the Arabic language is required for this course.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I am excited to explore with students the textual and archaeological traces of the Abbasid Caliphate and to teach students how we might examine these materials to understand this period in Islamic history as well as to think through how this historical legacy still matters to people today.

HIST 364: Europe in the Later Middle Ages

Instructor: Dr. Josh Timmermann (he/him/his)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

This is Charlemagne, who died in 814, well before the starting point of this course. Yet even as this Karlsbüste is representatively, and also in some sense literally, the Frankish emperor (given its function of preserving a physical relic), it is also emphatically not Charlemagne. It is, in stunning physical form, a mythic idea of past greatness; a projection of present majesty and future imperial glories; and a vivid encapsulation, pregnant with meaning, of a particular moment in Europe’s later medieval political history.

What can students expect from Europe in the later Middle Ages?

Students can expect to study a diverse selection of primary sources, from medieval theology and historical writing to love letters and a virtual tour of a medieval cathedral. The journey will be illuminated by up-to-date scholarship rethinking “traditional” conceptions of the later medieval world.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I am most looking forward to seeing and building upon what students already know (or think they know) about famous later medieval events or phenomena, such as “feudalism,” the Norman conquest, the Crusades, the Mongol invasion, and the Black Death.

HIST 400: The Practice of Oral History

Participants of the ''Punjabi in BC'' oral history project.

Instructor: Dr. Anne Murphy (she/they)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

The people shown in this composite are participants of the “Punjabi in BC” oral history project, which documents the history of the life of the Punjabi language in British Columbia through interviews with K-12 educators, activists/advocates, journalists, and students.

What can students expect from HIST 400: The Practice of Oral History?

The class covers methodological issues in the study of history and the role and ethics of oral history, technological and methodological approaches to oral history recording, and the history of Vancouver and British Columbia. Students will complete weekly readings, participate in a collaborative workshop to develop their own oral history final projects. The final project can take many different creative or academic forms, as long as they relate to the class content. There are two short writing assignments: one on the ethics and practice of oral history, and one other on course reading.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

I have taught a version of this course before that focused on South Asian and Punjabi oral history – “Documenting Punjabi Canada” – and am excited to extend the scope of the course to embrace a whole range of histories and communities.

HIST 490R: History Through Photographs – Exploring Photographic Archives

Filing system for the 107,000 photographs commissioned by the Farm Security Administration in the collection of the Library of Congress.

Instructor: Dr. Kelly McCormick (she/her/hers)

Why did you choose this image to represent the course?

Archives are crucial sites for providing access to historical materials. They are also reflections of systems of power. In this photograph, we see how the US government once thought of the Farm Security Administration photographs as a potential library that could be utilized by publishers and the public. This collection asks the question, “how might we turn to the photographic archive as a record of past ways of thinking to address and restore histories that have been ignored?”

What can students expect from this upper-year seminar on photographic archives?

Each week, visits to photograph archives will be paired with related readings that will help frame the collections we view. Students will be expected to write a research paper based on materials from one of the archives we visit or write reparative histories that might include adding more information to incomplete archival entries and reflecting on the role of historians in the archive.

What makes you excited about teaching this course?

In this class, we will visit a photographic archive based in Vancouver (almost) every week! We will explore the range of photographic histories preserved in this city through photographs, and critically examine the ways that archives are constructed. Through deep dives into the archives of the Vancouver Police Museum, the Museum of Vancouver, the City of Vancouver Archives, the Vancouver Maritime Museum, the Museum of Anthropology, the Jewish Museum and Archives, UBC Special Collections, and more, we will ask how photographs record and make history. Together, we will make propositions for what new histories can be told through these archives.