Professor Henry Yu remembers speaking with his writing professor in his office decades ago as an undergraduate student at the University of British Columbia. The professor made an offhand comment that Yu “writes well for an Asian.”

Photograph by Denise Fong.

When asked today what inspired a new exhibit in Vancouver’s Chinatown that challenges the notion that Chinese-Canadians don’t belong in British Columbia—and more largely, Canada—Yu points to that moment in his former professor’s office.

Yu, now an Associate Professor in the Department of History at UBC, sits on the board of the new Chinese Canadian Museum that opened its very first temporary exhibit in Vancouver’s Chinatown in early August.

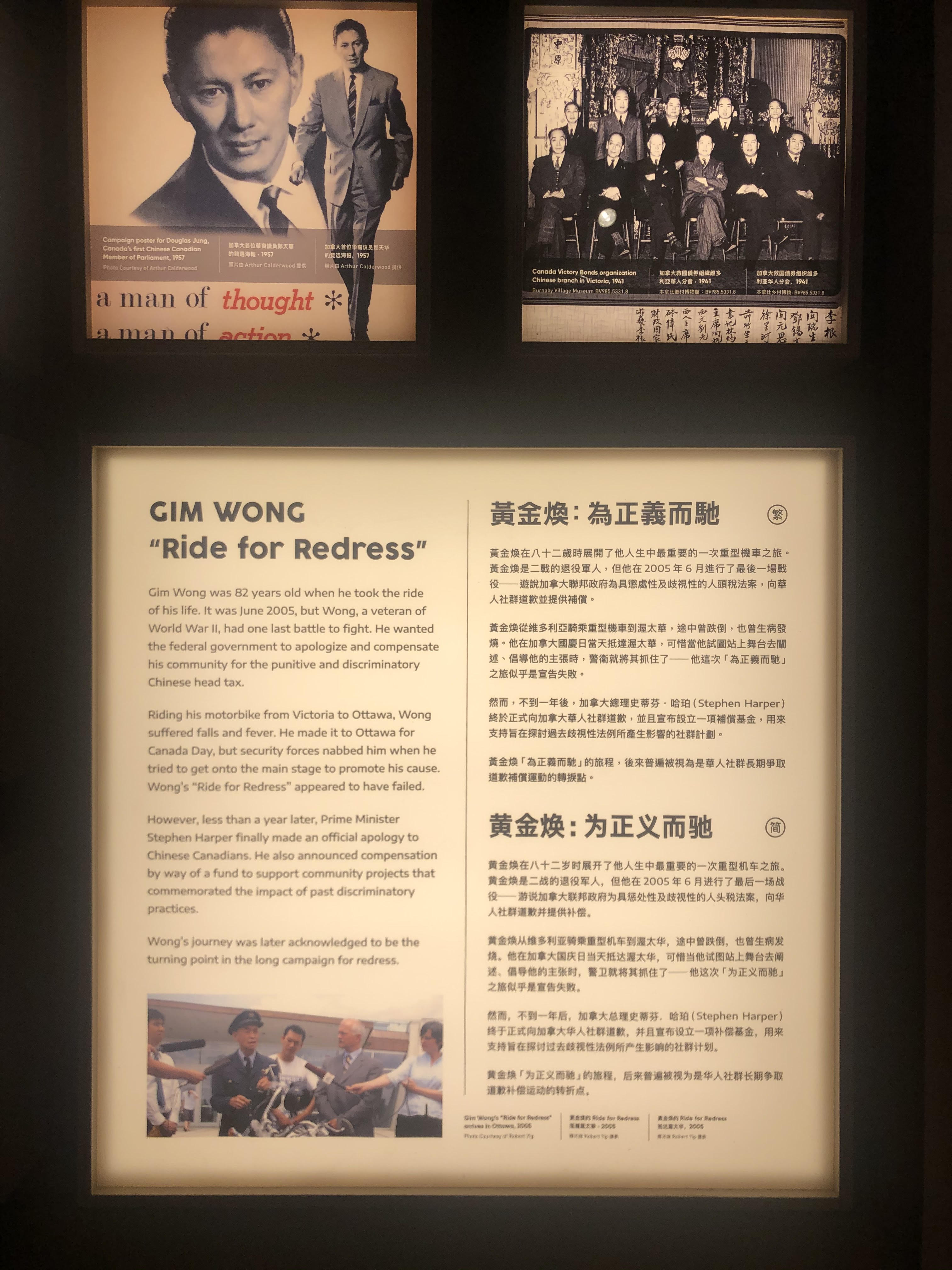

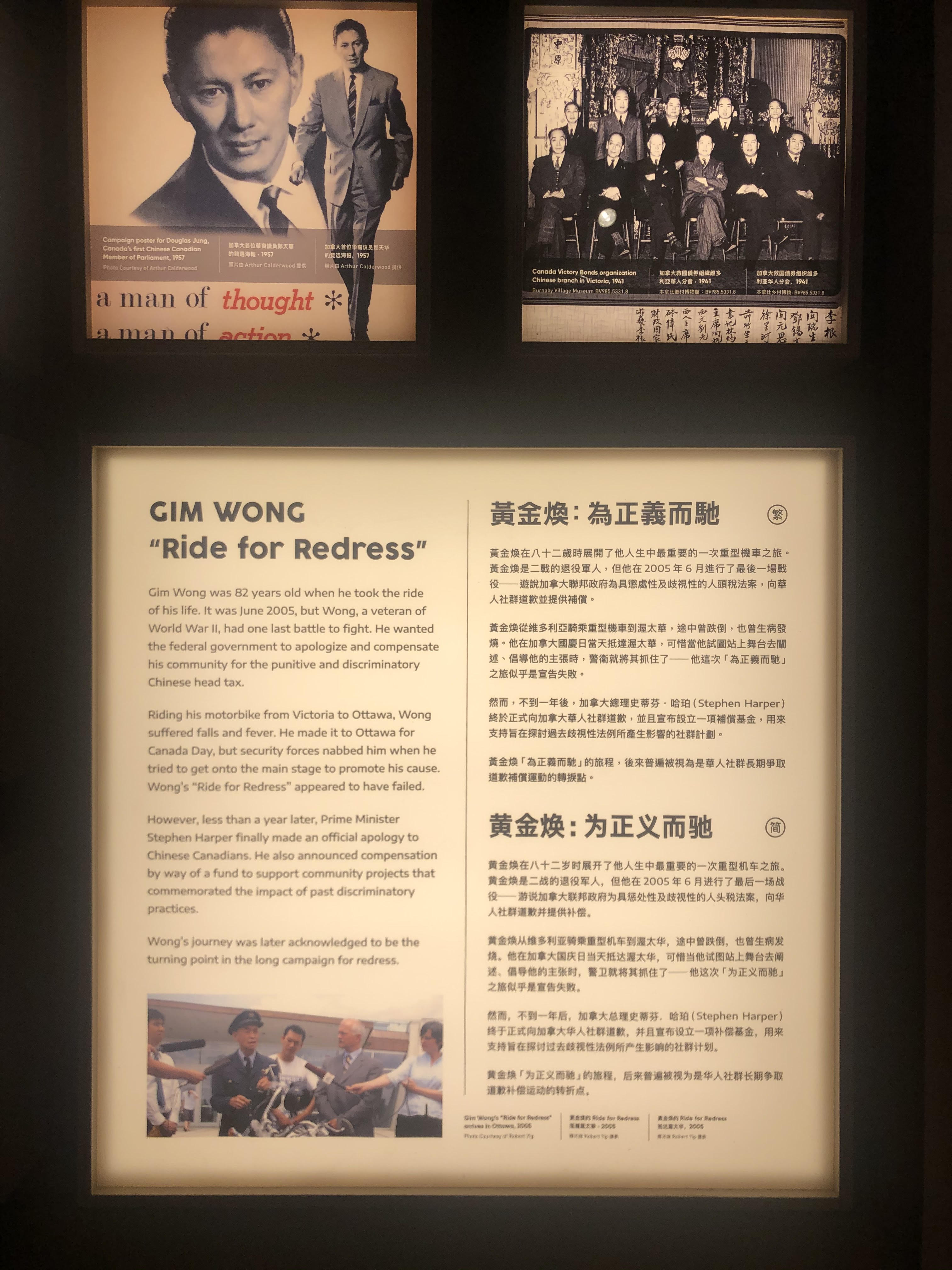

The exhibit boasts a plethora of stories, told through photos and videos of Chinese-Canadians across generations. The research materials were provided by UBC students who have worked with Yu over the last 15 years, who conducted interviews in Cantonese, Mandarin and English and translated the transcripts into each of the other languages. The exhibit includes both important and everyday moments in Chinese-Canadian history, and allows for Chinese-Canadians to tell their stories in the context of their struggles to belong as Canadian.

In 1872, as one of the first acts after joining the Confederation of Canada, B.C. stripped Chinese immigrants of the right to vote. They were also denied the right to enter the professions, including law, medicine and accounting. It wasn’t until 1947, after Chinese-Canadians fought in both the first and second World Wars for Canada, that they regained the vote despite the systemic legalized racism.

The exhibit’s resonant name, “A Seat at the Table,” refers to the struggles of Chinese-Canadians to be recognized as Canadian, to have a seat at the table alongside other Canadians.

It also refers to literally sitting at the table and enjoying Chinese food together, to happy memories and to the contributions such as Chinese restaurants and cuisine that Chinese-Canadians have made to Canadian society throughout the years.

Photograph by Wendy Yip

“The most important accomplishment of white supremacy is to erase you from the story,” says Yu. This is why we still have this idea in Canada that Chinese don’t belong. If you aren’t part of the story, how do you correct that?”

The translation-heavy aspect of the work UBC students have undertaken speaks to the exhibit’s decolonization of the space from the default language of English.

Photograph by Wendy Yip

Students interviewed subjects in the language they felt most comfortable speaking in—Cantonese, Mandarin, or English—and then subtitled the edited films in English, traditional written Chinese characters, and simplified Chinese characters. This exhibit treats the three languages equally in print, which, according to Yu, is in and of itself, an anti-racist act.

“It’s a colonial practice to value monolingual (that is, ‘English only’ speakers),” says Yu, who is a second and fourth generation Chinese-Canadian. “If you’re multilingual, you can’t speak in a way that betrays that you speak other languages. A student growing up here learns to be ashamed to speak with an accent, or even be afraid to know another language.”

Photograph by Wendy Yip

Along with Yu, the exhibit’s co-curators included UBC alumna Viviane Gosselin of the Museum of Vancouver, UBC PhD candidate Denise Fong, and a committee of community and research advisors that included Yu’s history colleague, Professor Tina Loo. Their emphasis in the exhibit on the rich lives of Chinese-Canadians is deliberate. Rather than viewing Chinese-Canadians only for their suffering as the victims of racism, Yu says, it is important to recognize that Chinese-Canadians survived and thrived despite the challenges of not being recognized as Canadian—challenges they still face.

“Historians are keepers of the stories of the past. To include stories of those who are forgotten, excluded and deliberately framed as uninteresting and alien, is itself an anti-racist act,” says Yu.

“We are also inspired by how many Chinese migrants saw themselves as guests in Gold Mountain. Perhaps a better history of belonging in Canada is one where all of us who aren’t Indigenous understand ourselves as perpetual guests on Indigenous territory. That’s part of decolonizing the story of BC. That’s why this exhibit exists.”

Read more about the exhibit here.