Bakers at Work. Source: Inventario Nº 245615, Photographic Collection, Archivo General de la Nación

Bridge to Argentina is a brand new multilingual virtual museum, created in collaboration with the Argentine Museum of Immigration. Its goal is to narrate the history of immigration to Argentina, present scholarly research in interactive exhibits, and to build connections across the world. If you want to listen to classic tango songs or radio shows or go on a virtual walking tour of immigrant monuments all over Buenos Aires from the comfort of your home, then Bridge to Argentina is the perfect resource for you.

In this Q&A, we sit down with its curator, Dr. Benjamin Bryce, an associate professor of history at UBC, for an inside look at the online exhibit and what’s to come. Read on for a glimpse into Argentina’s immigration history and how the museum project came to be.

For a project so aptly named Bridge to Argentina, in what ways does it connect academic research with the world outside of it?

I firmly believe in public history. I regularly teach a fourth year seminar that engages with community institutions and pushes students to create public-facing research projects. This virtual museum is important to me because it seeks to connect academic research from Argentina, North America, and Europe, with a range of public audiences.

As visitors make their way through the virtual museum, what are some key ideas you want to highlight?

Monument to France (Buenos Aires), built for the 1910 Argentine Centennial of Independence. Photo by Benjamin Bryce

What a visitor gets out of the exhibits depends on the viewing language they choose. It also depends on aspects of the visitor’s existing relationship to Argentina. The English version of the exhibition was written thinking of those who might be looking to visit Argentina, which might include tourists, students of Latin American history, and migration researchers elsewhere. With this audience, we want to share scholarly research about migration to Argentina in a more accessible way, including with audio clips, pictures, and videos.

For an Argentine audience, we want to challenge a lot of myths about the country’s history. We want to show it was more complicated, more nuanced, and more hybrid than how it is normally remembered. The Italian exhibit, which is trilingual, speaks to something also central in Italian historical consciousness, namely that a lot of Italians went to Argentina. By showing the hybridity, the two-way flows, and the Argentine-ness of Italian migration, we hope to unsettle a different set of ideas about history.

What is the relationship between Bridge to Argentina and the Museo de la Inmigración (Argentine Museum of Immigration)?

When Mirta Roncagalli, a UBC PhD student in Hispanic Studies and I started with this idea in early 2022, the support of the museum’s director, Marcelo Huernos, gave the project legitimacy. At the exhibition level, part of the Curator’s Choice section of the virtual museum is based on current exhibits at the Museo de la Inmigración, and there are some videos and pictures in the online Italian exhibit that were created by the museum and used in a previous exhibit.

Disembarking in the Port of Buenos Aires Source: Inventario nº 215763, Photographic Collection, Archivo General de la Nación.

Tango is a popular dance and music genre featured in Bridge to Argentina. It originated in Río de la Plata, and is a product of immigration and the meeting of different cultures and languages. What are some other creations or artifacts that are direct products of immigration?

You are talking about the article about tango in the Italian exhibit. While perhaps more a direct importation than an example of cultural creations, there is also an article in the exhibit on Italians about how opera singers came to Argentina and had illustrious careers.

Language is a common and easy example of how human mobility leaves its traces generations later, even as it adapts to new spaces. There is a long list of Italian words that have become integrated in Argentine Spanish. Some examples are fiaca, laburar, pibe, and capo. I personally only realized recently that fiaca will help me express a pretty complex feeling in Italy too.

Religion – both institutions and ideas – is also a direct product of immigration. The existence of synagogues, mosques, Orthodox and Protestant churches, and Gurdwaras are all the direct result of immigration and all would have been pretty close to non-existent in Argentina had there not been immigration since the mid-nineteenth century.

Bridge to Argentina currently has a fantastic exhibit on Italian migration. Are there plans to expand the virtual museum to include immigration history from other parts of the world in the future?

There sure are! We have discussed plans with the Maritime Museum of Barcelona to develop a similar exhibit about travel, titled “Let’s Talk about the Voyage,” as something crucial to not only the immigrant experience but also to understanding immigration patterns and how states regulated and excluded certain migrants before they ever boarded a ship. We plan to build a stronger bridge with some Italian institutions based on the current project. We also hope to reach out to the Deutsches Auswandererhaus in Bremerhaven, both to talk about the travel exhibit and perhaps also to develop an online exhibit related to German and Jewish migration to South America.

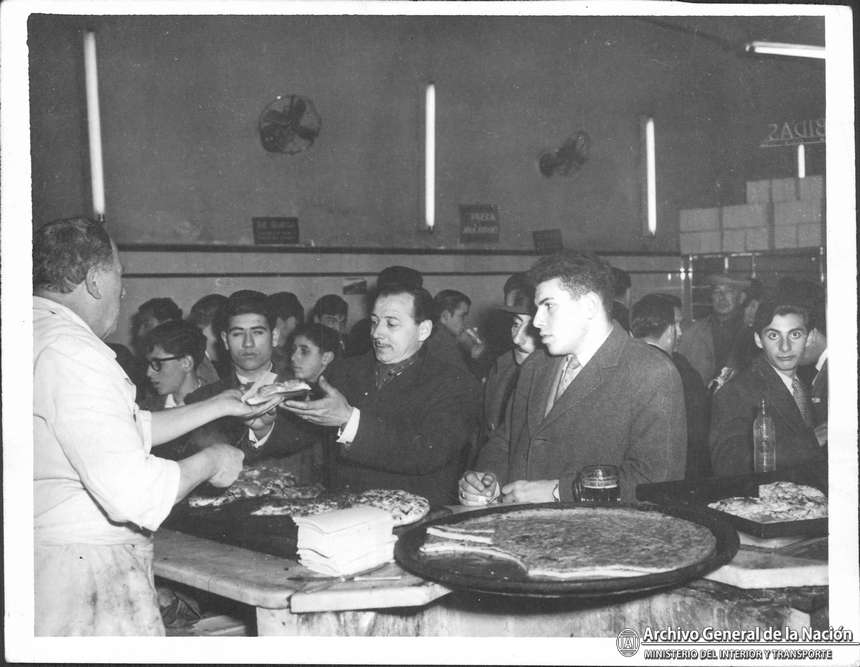

Enjoying Pizza, Empanadas, and Fainá at a Buenos Aires Pizzeria Source: Inventario Nº 277606_A, Photographic Collection, Archivo General de la Nación.

In an answer to a previous question, you had said one of the goals of the museum is to challenge myths about Argentina’s history. Do you have specific examples in mind?

One of the museum’s short term goals, one that also aligns with a priority of the Museo de la Inmigración in Buenos Aires, is to develop an exhibit about how Indigenous peoples in Argentina have spoken about European immigration since the nineteenth century. In this case, rather than building bridges, we sort of want to burn down a series of bridges or pillars that support national narratives of immigration. Argentine discussions about the arrival of millions of European workers and farmers are rarely connected with discussions about systems of violence, marginalization, and dispossession. Building on the linguistic focus of this virtual museum, we intend to work with several communities to translate the Indigenous voices we find in Spanish-language archival documents into the languages of these Indigenous interlocutors, such as Mapudungun, Tehuelche, Rankülche, Qom, and others.